Self identity and “space”

We first come to know ourselves in and through the “spaces” and places which form the backdrop of our childhood.

Not idealized space, or remembered space (that comes later), but actual, lived spaces which become both fixed and familiar as the context and limits of our personal “world.”

Additionally, our sense of self as understood (and later conceptualized) becomes rooted in memories that are anchored to our own particular past which are found (and bound) by remembered spaces and times.

For example, consider your childhood bedroom, your grandmother’s kitchen table or the where and when of your first kiss. Each remembered locale carries with it emotional weight and significance (or not) based on the pleasurable or painful memories of events which were experienced in those places by you. Simply put, these remembered places become the ones which are treasured or locations to be avoided. Our memories, if you will, associate the “where” and the “when” of our experiences, which is why there are no neutral spaces found in memory. Places and spaces without emotional significance are simply not remembered.

What this means is that emotionally significant spaces become internalized “places.” And because they form the contextual fabric for our own personal history (and sense of personal identity) they are emotionally CHARGED.

As such, remembered places and spaces have weight, gravity.

The stories from your past that you remember and which you hold onto as so many precious “objects” rooted in your past all take place in some sort of PERSONAL space.

And the memories of your own, special “places” may be remembered (and therefore felt) very differently by other people in your life who “lived through” those self-same spaces. Your favorite grandmother’s kitchen might have far less emotional “weight” for your brother or sister (for example) simply because the memories (or lack thereof) of that particular place will be different for THEM based on THEIR own personal experiences of what seems, on the outside anyway, as the same “place.”

Which is to say, the places we remember are never reducible to three dimensions and a catalog of the room’s contents.

This means that your “world” was experienced and framed by a series of places and spaces which were (or became) comfortable and familiar to you (or, likewise, places decidedly uncomfortable). They became the cherished places (or ones to be avoided) which formed the backdrop for what you came to recognize as a sense of “home.”

And these places, both the comfortable ones and the spaces which made you uneasy or fearful, formed the actual LIMITS of your lived world, so to speak. Which is why…

“Inhabited space transcends geometrical space.”

~ Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

The implications of this understanding underpin the simple fact that external spaces and places become internalized with emotional significance based on the particular events of our lives experienced and interpreted by each one of us over a period of time within a given CONTEXT. In other words, each location as the root and ground of experiences that “left their mark” on you by way of the accumulated emotional significance of particular events in your personal history become anchored in nostalgia when remembered and are, for you, emotionally charged when revisited in “real” time.

Which is to simply say, we are never indifferent about the spaces we occupy.

And this means that the external “spaces” of our life and our “world” are invested with feeling. And therefore, meaning.

In fact, each of the spaces of our “world” forms both the backdrop and context which helped to define who we considered ourselves to be while further shaping our ideas and beliefs about the world in which we find ourselves.

Which is to say, WHO we think we are has a lot to do with WHERE we grew up (i.e. conditioning) while also shaping where we choose to be right now, either as a place which resonates in a manner similar with comfortable spaces from our childhood, or in contradistinction to those very same spaces.

Simply put, the spaces that once “confined” us are also the self-same spaces which helped “define” us.

An encounter of limits

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

~ Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Every system is circumscribed by rules (or norms) which form the limits of understanding or operation for that particular system.

For example, in your elementary school math class you were most likely taught that it’s not possible to divide any number by zero. And if you doubted or questioned this fact and tested this with rule out by using a calculator you would get some sort of error message as the “answer” to your operation, such as “undefined” or “error” (depending on type of calculator you were using).

Without doubt you did not get an answer of “zero.”

Simply put, this particular operation (division by zero) cannot be done. And the reason it’s impossible to “solve” this sort of problem is because there is no definition or rule for how to handle this operation. In short, this particular example, exists outside of (or beyond) the rules of the game, so to speak.

In other words, this particular operation forms what I like to call a “limit situation.” It’s like bumping up against a wall or boundary which prevents you from realistically (or logically) going beyond.

Now, returning to another example from math class (this time from high school) it’s possible that you learned about another potential “limit situation,” this time found when dealing with negative square roots. I’ll do my best not to bore you with too much math. Let’s just say that in math each operation has an opposite operation: subtraction as the opposite of addition, division as the opposite of multiplication. Hopefully you get the idea. Well, in math there is an operation called “squaring” where you multiply a number by itself, so 3² = 3 x 3 = 9.

With me so far?

Good. Now, the opposite operation of squaring is taking the square root (where this symbol – √ – gets used). So the square root of 9 (or √9) = 3, because 3 x 3 = 9.

But here’s where a problem arises, and it has to do with negative numbers. You see, if you square -3 you end up with positive 9, not negative 9 (-3 x -3 = +9). And this happens because the rules of math state that a negative number times a negative number equals a positive number. So what’s the problem? Well, what happens when you try to take the square root of a negative number?

It would seem that, like the case of dividing by zero there no possible solution. But not so fast.

You see, in math you’re allowed to make substitutions of equivalent values (provided you follow the rules properly). So when you run into the case of the square root of -9 you were taught that you can substitute the square root of -9 with the square root of 9 x the square root of -1. I already showed you that the square root of 9 = 3, so now you’re left with 3 times the square root of -1. And this, you might think, still presents a problem. In this particular case, however, there’s one more workaround that allows you to complete the answer. And this is where “imaginary numbers” come in. You see, mathematicians define the square root of -1 as the imaginary number i. By “simply” substituting the imaginary number i for the square root of -1 you are able to keep “solving” the problem of negative square roots. So, from the example above the square root of -9 becomes the square root of 9 times the square root of -1, which becomes 3 times the square root of -1, which becomes 3 times i, giving you the perfectly correct (and acceptable) “mathematical” answer of 3i.

Simply put, you were given one defined “thing” in order to replace another undefinable “thing” which allowed you to further solve and simply these types of mathematical problems.

Yes, I know it sounds a bit crazy, forced and totally “made up.” But there you have it.

So what does all this have to do with limit situations?

ALL systems which we are taught (by teachers, pastors, parents, etc.) are really systems of THOUGHT. As such, they are ALL rule driven.

What’s more, systems of thought are DEFINED by their set of rules. This include, of course, religious DOGMA and social CONVENTIONS. And this means, in truth, that failure to comply with the rules of a particular community MEANS that we are either considered to be “wrong” or, more often than not, find ourselves outside the thought community in which we were raised (i.e. excommunicated or shunned).

Which leads to the final point. The “rules of the game” which DEFINE these “mental” spaces were created at some point or another and passed down (i.e. “enforced”) by “proper” education and tradition.

In some cases when we were taught the rules of the game it was explained to us that we could go no further (i.e.”don’t question your faith”). At other times we were taught socially “acceptable” workarounds or ALLOWED “exceptions to the rule.”

And this leads us to the final point.

When we encounter limit situations in our world it presents us with an OPPORTUNITY (possibly best expressed by the Ancient Greek word κρίσις – or krísis – which meant a “separating, power of distinguishing, decision, choice, election, judgment, dispute”).

Quite simply, an encounter with limit situations can show us the inadequacy of our rule-driven systems. And they can show you the absurd lengths people go to in order to define and enforce the “rules of the game.” And more importantly, they provide you with the opportunity to QUESTION the very limits that define your world.

A questioning which may pull or tug at the established status quo.

Limit situations, doubt and “crisis”

“we cling tenaciously, not merely in believing, but to believing just what we do believe.”

~ Charles S Peirce, Philosophical Writings of Peirce

There are plenty of real life examples where we run into the confining limits of worldviews that we inherited as part of our heritage and upbringing. Worldviews which are often (by definition) limited and limiting.

For example, when I joined the Air Force at seventeen years old I was quite literally thrown into a group of other guys who were all pretty much older than myself, from all different walks of life and from different parts of the country. And these other people, for the most part, had quite different views of the world than I had and considered “normal.” And this difference should really come as no surprise, especially given difference in age, upbringing, cultural influences and religious traditions.

Yet, these people all seemed normal and rational enough to me.

And that was my first real DIRECT experience where I realized there were other ways of looking at the world, other ways of making sense of our world and our place in it.

Now, I didn’t always agree with these other views.

That’s not the point. The point was that how we view the world (and therefore make sense of our place in this “space”) has everything to do with WHERE we grew up and HOW we were raised. Our particular views of the world have everything to do with inherited “wisdom” passed down to us by parents, family members, school and the particular religious and cultural traditions we happened to be born into. In short, where we grew up and the spaces that formed the backdrop of that upbringing has formed the very limits of what we would consider “normal.”

Now, the key question remains: since our dominant assumptions and thoughts are conditioned, where, when and how does the questioning begin?

In my example above, it was travel at a fairly young age away from my home, my town and my surroundings that enabled me to encounter sane, rational people from different walks of life who thought differently than I did about a range of issues. This encounter with “other” ways of thinking about things or views on the world became a cause for DOUBT. In other words, faced with a different take on reality (even a little tiny slice of it) caused me to doubt the authenticity of seeing the world through the particular lens of my own upbringing.

But that’s not always the case.

In fact, faced with constant points of contradictions of which our world is filled there are always opportunities for questioning the grounds that make up our assumptions.

For example, back in third grade I attended a Catholic school, and we were being prepared to receive “First Communion.” In case you weren’t raised in this religious tradition, at the age of seven children have reached the “age of reason” and are therefore capable of committing a sin. Based on this logic, they are prepared to confess their sins to a priest.

Now, since we had religion class every day we had heard of the word “sin,” but usually in the context of the biggies – killing, lying, doubting the existence of God, etc. But what type of sins could a seven year old child commit?

Well, that’s what the nuns were preparing us for. And in our case they listed a bunch of minor transgressions to confess to the priest, such as using bad language or fighting with siblings. During the course of this instruction the notion of jealousy came up, such as “don’t be jealous of your brother or sister” along with some examples of what jealously was. Now, in earlier discussion on the “nature” of God we had been taught that God was a “jealous God.” So on hearing that jealously was a sin and thinking back to the line that “God is a jealous God” my hand shot up with a burning question — “how could God be a jealous God if jealousy is a sin.”

Here you have a real-life example of belief running into a point of contradiction. One, mind you, that my teacher couldn’t answer. In the end I was taught that questioning the nature of God, like doubt, was also a sin. So at least I now had something to confess when it was my turn.

But the simple fact remained.

It is in the encounters with flawed logic at the periphery of our world views, the boundaries of what we assume to be true, of what we hold to be the “normal” view of the world that we can begin to question the assumptions.

In other words, the fact of questioning begins with an encounter with the flawed logic that makes up the fabric of our world.

Provided, of course, that you’re not sleepwalking your way through this life.

Stirred by the “irritation of doubt” you are ultimately faced with three options concerning what you used to believe in so strongly:

- you can treat the occasion of doubt as an “exception to the rule” and include in your worldview (as an outlier),

- you can ignore the occasion of doubt and cling even more tenaciously to your inherited beliefs and choose to live an a “bubble of belief,”

- you can begin to question the grounds of your belief(s)

Essentially, that’s it people.

Faced with any idea, belief or life situation that doesn’t fit into the well-defined spaces of what you consider “normal” there are only one of three possible outcomes. And unlike the five stages of grief (as outlined by Elizabeth Kubler Ross) there is no progressive working through of them (or “ascension”), as if some process unfolds naturally. Quite simply, we tend to CHOOSE one of the three outcomes as a personal choice born out of habit and, possibly, temperament.

Which means you never have to expand your boundaries if you don’t want to.

And most people don’t.

Ego, identity and “your” world

“That the world is my world, shows itself in the fact that the limits of the language (the language which I understand) mean the limits of my world.”

~ Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

The spaces you inhabit mark the boundaries of your world in the real sense that you come to know yourself with respect to those places where you feel most comfortable. So the “MY” emphasized in the quote above is not one of possession or ownership. It’s not a question of your “owning” your world.

Why is that?

Why do those confines of “my world” as outlined by habit and belief seem so comfortable to us? Because it becomes a question of IDENTITY and security.

Ego as a construct of enclosed mental space from which we operate.

You come to identify yourself as the person who lives and moves within the boundaries of space and place that form the limits of your world. In other words, your conception of your “self” is rooted in the context of the places most familiar to you and ones which you identify as “being at home” in.

So in a very real way external space becomes internalized.

Like the kind Pakistani family (friends of my wife) who live in the next town away from us. They have lived here in the United States, and their three children were all born here. But they live almost exactly as if they were living in a village in Pakistan. And the fact that this happens is not so surprising, really. Because the spaces that occupy our world are not empty spaces. They are filled with “flavor” — familiar sounds (language, music, movies, prayer) and familiar smells from the kitchen. The language you speak and the foods you eat all “mean” something to you, all form some basis of your identity.

The spaces and places of your life become internalized while forming the backdrop for your daily interactions with others. As such, personal identity always transcends actual “geometric space.”

In short, your life is filled with people who on some level or another we are “related to” — and by related to I mean in relationship. And this relating one to another (or one to many) takes space (e.g. happens) in the lived-through and emotionally charged spaces of your life which are not abstract, but actual. And actual spaces have depth, texture, a “mood” you feel without having to describe it through words or language, yet palpable nonetheless.

Typically we use word like “relationship” to talk about romantic relationships or our dating “status,” as in “I’m in a relationship.” But the fact of the matter is that our life is one OF relationship, or having to “relate to” the people around us, all the time.

Or, of choosing not to relate. To remain closed off from others like an actual (or virtual) hermit.

And it is our active “relating to” others in the spaces that make up our life that give emotional “weight” to those spaces. What’s more, those spaces can be positively or negatively “charged” or weighted with our emotional responses to them based on the people and circumstances of our interactions with the people in those spaces. Quite simply, our outer world shapes us – our feelings about those spaces become internalized and mark the boundaries of what we feel comfortable with. Those external and familiar spaces define, in a real way, our “comfort zone.”

In fact, the origins of our “comfort zone” begin in those spaces where we felt comfortable, protected. External boundaries of our world have become internal “boundaries” of thought.

Where we live (and lived) has become what we believe.

“You know what space is. There is space in this room. The distance between here and your hostel, between the bridge and your home, between this bank of the river and the other; all that is space. Now, is there also space in your mind? Or is it so crowded that there is no space in it at all? If your mind has space, then in that space there is silence and from that silence everything else comes, for then you can listen, you can pay attention without resistance. That is why it is very important to have space in the mind.”

~ J. Krishnamurti

Is it any wonder why people don’t respond well to change?

We grow up and have been school in the language of conformity. In fact, our upbringing and education is focused primarily on “helping” us fit into the framework of a society where the boundaries have already marked out for us.

For example, look at this list of common expressions:

- “one hand washes another”

- “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours”

- “blood is thicker than water”

- “you do for family”

- “there is strength in numbers”

- “tow the line”

- “don’t rock the boat”

The last one on the list (a list, by the way, which took less than 30 seconds to compile from memory) was a favorite of my mom. I heard this one many times while growing up in my parents house, and always in response to my asking a question of why we did certain things that didn’t seem to make much sense to me. My mom’s response what simply that you do what you have to do, even if you don’t like it, because that’s “what’s expected of you.”

But why would the questioning of certain assumptions of behavior on my part be equated with an expression that basically means “don’t capsize the boat?”

Because “norms” of behavior provide us with a sense of security.

And our “identity” as people tied to a place and the “spaces” outlined both by familiarity (a sense of “home”) and of fitting into this framework set the norms for how we come to see ourselves.

And feel ourselves.

Belonging to a “tribe” and feeling “at home” provides you with a sense of self. And a sense of security. Because “belonging” means, by definition, belonging to some place and some group.

But the fact of the matter remains that the boundaries of self-identification are not consciously chosen by you. It’s “fit it” or “get the hell out.” Failure to conform to the standards of your family or other “group” (tribe, ethnic group, religious tradition, etc.) in which you happen to have been born leads to ostracization or exile, either by the group of self-imposed.

In other words, you don’t have to move away from familiar spaces and places to run into the limits of your “world” which can, provided you’re attentive enough to pay attention to those contradictions and conflicts when they arise in your life. The dichotomies, if you will, between what you were taught to believe and what you’ve observed in the “world” around you.

In my particular case it started with the contradiction of being taught to fear a jealous God and being told that jealously was a sin. And witnessing my mom cry every Christmas Day after visiting my dad’s side of the family, and asking her why we even bother to go there since they make her cry only to be told that “you do for family.”

Those contradictions and logical conflicts caused me to start QUESTIONING.

And literally everything.

Because if the nuns could be so flawed in their logic of a jealous God who is supposedly perfect, yet who seemingly sins too, then what else could they be wrong about? And if my mom’s “doing for family” means you give family members a “pass” by simply accepting (or putting up with) bad behavior simply because you “happen” to be related, what else could she be wrong about.

In both cases, to ask a question threatened the status quo. The nuns told me that asking a question about God and my religious tradition was a sin, yet they said that I should use my God-given intellect in math class. More contradictions.

So the fact of the matter is this. We grow up and come to understand ourselves through the comfortable confines of emotionally charges spaces. And these same places and spaces provide us with plenty of opportunities to question the “friendly” and familiar limits of our world when we run into conflicts and inconsistencies.

But the CHOICE to ask the question, serious questions about our “place” in the particular spaces in which we find ourselves is entirely up to us.

Simply put, we can outgrow the beloved spaces in our lives, and our relationship to familiar places can undergo change as well.

In any or all of these situations external factors can cause a radical change or adjustment to the limits of your world. Places that you visited often may no longer be in play. Or the changing dynamics might force you to reevaluate those spaces and your relationship to them.

Expansion of our space can be scary, threatening to take away familiar fixtures that mark the comfortable boundaries of our world. As the comfortable limits of your world (and of yourself) are modified or enlarged the experience can be frustrating or deeply unsettling.

This happens because a change in our “outer” world has a concomitant change on our inner “space” as well.

But so far the examples cited above describe changes that happen to us. Changes that are, for lack of a better word, forced upon us by time or circumstance.

There are the times in our life when we recognize that our world is too “small” or that the boundaries of our external “world” need to be shifted, enlarged or changed altogether.

Habit – seeking the familiar in our thoughts, in our routines. Much like we seek familiar spaces that make us feel safe, so too our mind “inhabits” regions which are comfortable and help us feel safe. Our sense of self as defined within the confines of what we think, what be believe, what we understand about ourselves.

Because given the opportunity to expand one’s boundaries and overcoming any sense of “loss” or discomfort associated with the expansion of one’s boundaries, it is within your power to allow something wonderful or beautiful to take root there.

And that’s the key.

Given a greater sense of freedom, of expanding one’s boundaries, what will you fill it up with? Or better yet, what will now be able to grow in your now expanded inner space? How will your mark the boundaries of your new “world.”

So what is the outcome of all that space?

It is through space and silence that we can turn within to discover truth. Only by being alone, in quiet, can we plumb those interior depths to discover the foundations of our TRUE self.

“You cannot be a light to yourself if you are in the dark shadows of authority, of dogma, of conclusion.”

~ J Krishnamurti, This Light in Oneself

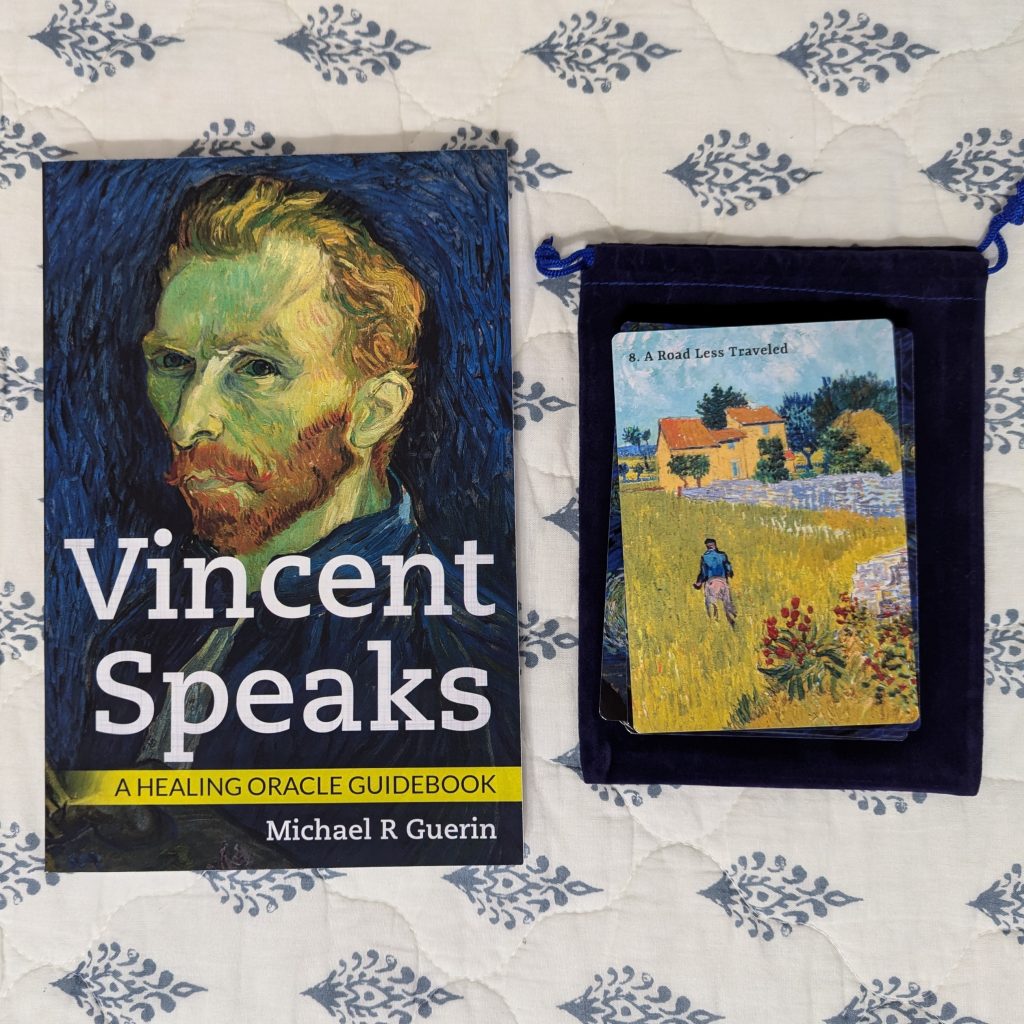

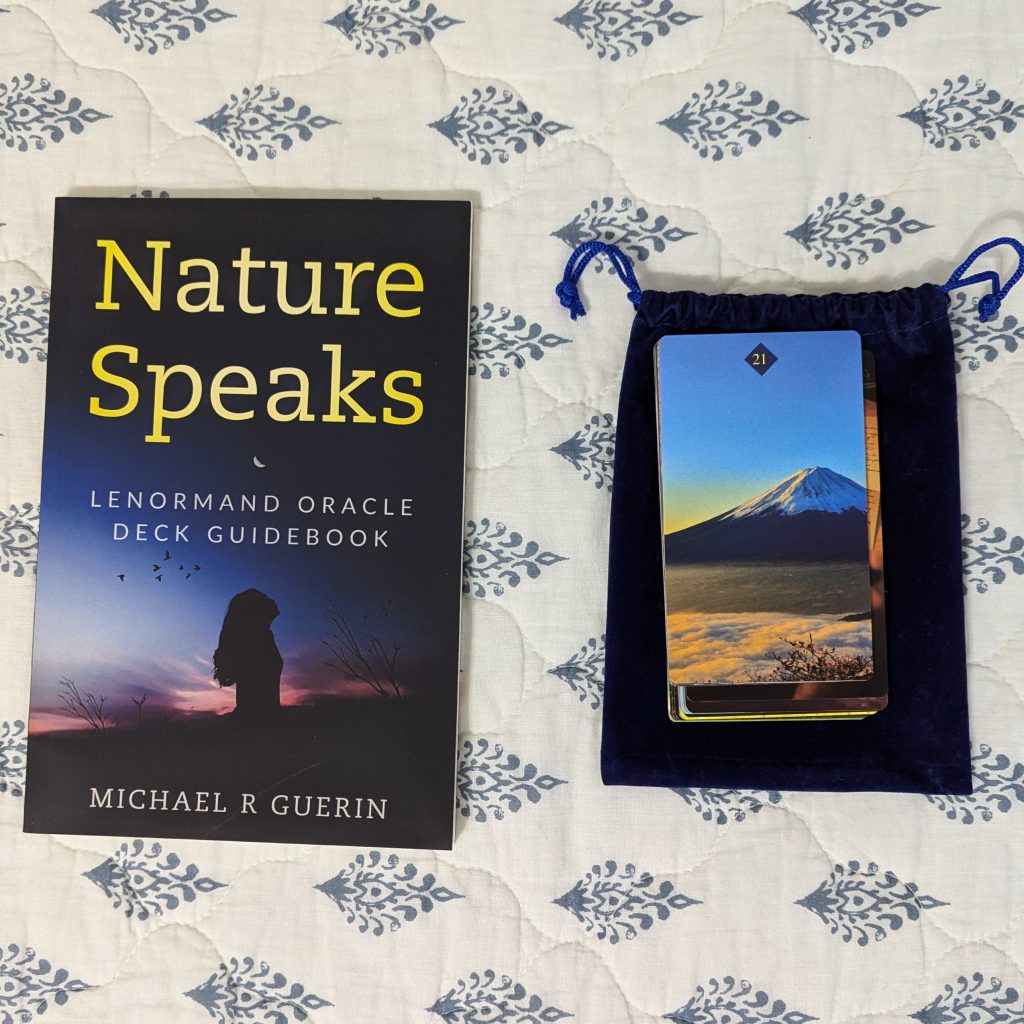

* The heart card (#24) comes from the Nature Speaks Lenormand Deck. If you would like to get your own deck of cards please click the link.